Jun 19, 2018

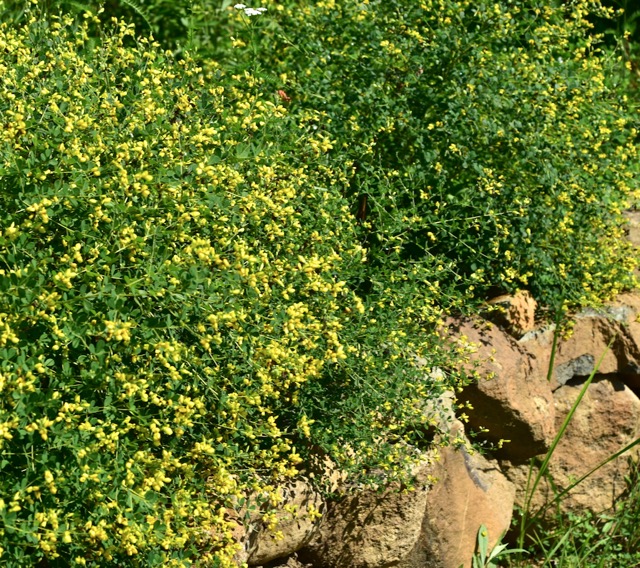

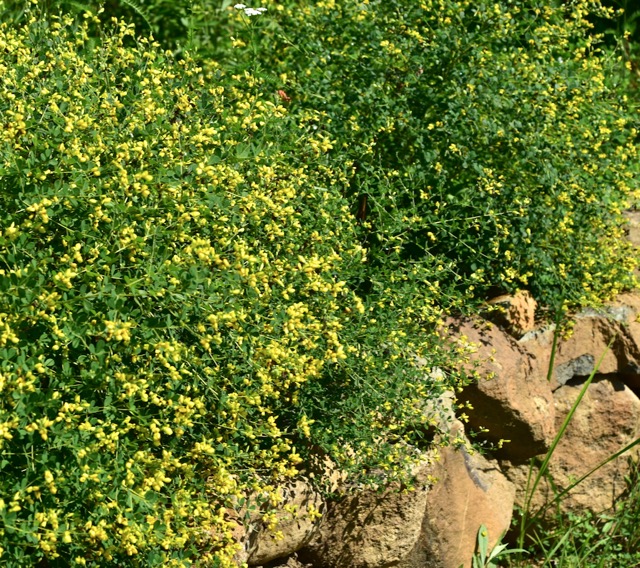

Yellow false indigo, the wild Baptisia tinctoria, is spilling over the wall of our Pineywoods pathway now, alive with bees. It’s a rounded shrub topping out at about two feet in height and width, and it makes a nice border.

Better known perhaps are the stately three-to four-foot tall wild indigos that produce dramatic spikes of bloom in blues or yellows for the middle to back of the border. “Carolina Moon,” in this photo, is a found hybrid of B. Sphaerocarpa and B. alba (native, but not to here; therefore, not blooming here).

More common in the wild and in gardens is Baptisia australis, the blue form. The genus name is from the Greek word bapto, meaning to dye. The common name refers to its Native and Early American use as an inferior substitute for true indigo in making blue dyes; both blue and yellow baptisias were so used.

Whether round or tall, yellow or blue, the plants share the blossom and leaf forms that readily identify them as members of the pea, or Fabaceae family. Not fussy about soil, they like it dry to medium, in full sun to part shade. As bees prefer blue flowers, but see the color yellow as blue—any baptisia is sure to please them.

If you like tall (up to 7 feet) spikes topped with white candle-like chandeliers, there’s a native plant for you, whether your site is in sun or shade.

Blooming now in rich soil and dappled shade below the Giant’s Stairs is Black cohosh, Actaea racemosa (formerly Cimifuga racemosa), AKA Bugbane or Black snakeroot. It blooms here for about three weeks in early summer against a dark background of soapstone boulders.

It’s odor is said to repel insects—but not the Spring azure butterfly, for which it is a host. Medicinally, the root has been used to treat many conditions, even snakebite, most notably women’s health issues.

If your place is in the sun, Culver’s root, Veronicastrum virginicum ‘Album,’ offers a similar aesthetic, and blooms at about the same time.

Unlike Black cohosh, which has a collar of basel leaves somewhat like peonies, Culver’s root has whorled leaves all the way up the stem. Deadheading can prolong bloom, and cutting back after bloom can result in a second late-summer flush.

Native over much of the eastern United States, Culver’s root has been used medicinally as a cathartic. A bird seeded it into our home garden years ago, and it has established and spread there so that we have plenty to share for the Piedmont Master Gardeners Spring Plant Sale each May.

May 1, 2018

Last week, we had hard rains on Monday and again on Thursday, and on trips around the quarries on the days following the rains, we discovered morels (and other fungi—see below). Here are three nice ones:

We collected about two dozen from along the trails, and then our friends Nina and Forrest expanded the search to our property adjacent to the Quarry Gardens. One of the ones they found was next to a showy orchid in bud:

They amassed quite a pile of large morels. Here are some of them with Nina’s hand for scale:

About an hour later we put our two piles together and used some for a really nice meal of morels with homemade ricotta gnocchi, peas and asparagus. The rest, separately frozen on trays, are bagged in the freezer for future delights.

Apparently the mycological community can’t agree on the number of species of morels (properly “morchella”). They are “subject to intense phylogenetic, biogeographical, toxonomical, and nomenclatural studies,” and according to Wilipedia the consensus of experts is that there are as few as 3 to as many as 30 species, but also that there are perhaps really 70 distinct species with several new ones reported from countries around the world. (And you thought that keeping up with the changing Latin names of wildflowers was tough.) Fortunately, all of them taste good, but you are cautioned to not eat them raw. If you want to know more about them, there is a website, morels.com, which keeps track of where and when morels appear and seems to have thousands of active followers.

In addition to the morels, we also found some less appetizing fungi like the three below:

We did not collect or try to eat any of these.

Apr 20, 2018

It’s getting towards the end of April, but the earliest spring ephemerals are just now blooming. We’re seeing Spring beauties, Virginia bluebells, Toadshade trilliums, Hepaticas, Rue anemones, Solomon’s seal, Bluets, several species of Violets, Golden ragwort, Spicebush, and Marsh marigolds. The featured photo is of some of the lovely Moss phlox near the starting trail.

Around the gardens, 35 “locator disks” have been installed, such as the one below at the Quercus Circle, to help visitors orient themselves to the trail map they can pick up at the Visitors Center. There are also two new exhibits up on the walls, but you’ll have to visit to see them.

Under the portico at the Visitors Center are two nice benches (of the now 13 around the quarries). A number of folks have found them a nice spot to have their bag lunch before or after a tour. The one on the right, of red maple, has been sponsored by the Piedmont Master Gardeners Association to honor Bernice, who was their president for a couple of years.

It now bears a plaque recognizing their gift.

In the lobby of the Visitors Center is an interesting artifact of quarrying times, a large cast-iron pulley wheel that once powered some large piece of belt-driven machinery, made into a coffee table.

This was given to us by neighbors and long-time friends Charles and Mary Roy Edwards, and a plaque now notes their gift.

And down near the second bridge, where the picnic grounds are found, is a beautiful octagonal table. (Sorry for the background: it’s still mostly winter around it.)

This was made by Forrest McGuire, lead contractor on the Visitors Center, and given to us, so there is now a plaque noting his gift.

The reason for pointing out these things is that many naming opportunities exist—everything from benches to trails to overlook sites to the Visitors Center, itself—for anyone who might be interested in becoming a benefactor at a level above that of “Friend of the Quarry Gardens.” Contact us, and we will cheerfully provide details.

Apr 8, 2018

Removing from our persons the first ticks of the season reminds us of the hazards they present—and our strategies for dealing with them.

(The featured photo of an adult deer tick is by Griffin Dill via University of Maine Extension.)

Both The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and The Rodale Institute agree that ticks dislike woodchips—one reason we encourage Quarry Gardens visitors to stay on the trails. And, indeed, when we stay on the trails, we aren’t troubled by ticks. There are fresh chips on all the trails, here along the Bern’s Run trail.

But we who must work in the woods and garden beds can’t stay on the trails, so we’ve taken Henry Domke’s advice. Henry and his wife Lorna run another mom-and-pop, private-for-the-public botanical garden: The Prairie Garden Trust in Bloomfield MO. Here’s the link to his blog post, which describes his method of tick-proofing garden clothing with Permethrin.

http://pgtnaturegarden.org/2016/03/preventing-tick-bites/

Permethrin is a synthetic version of a chemical produced naturally by the chrysanthemum flower. It is not safe to apply directly to skin. The U.S. military has used permethrin-treated uniforms since the 1990s, and civilian clothing based on the technology has been available since 2003.

It’s helpful to know that ticks don’t fly, hop, run, or even move all that quickly. Depending on the life stage and species, they quest for hosts anywhere from ground level in leaf litter to about knee-high on vegetation, and then tend to crawl up to find a place to bite. I’ve adapted Henry’s method to be a bit easier for me. I mix a .5% solution of permethrin (Sawyer is a brand that comes both pre-mixed in spray bottles or as concentrate), gather our work pants and socks outside, don long rubber gloves, and go to work, saturating pant legs and sock tops with the solution.

(Caption: Pants on the porch rail, socks on the chair arms. Note that pant leg bottoms and socks are in the shade—something about sunlight breaking down the Permethrin.]

Last year, I applied the solution as a spray; this year, I mixed a gallon of it in a small bucket and dipped the pant legs and sock tops—much easier. Then I drape the clothes over the outdoor furniture and porch railings and let them dry in the breeze. If I were more concerned about mosquitos and other insects, I would dip the whole garments, as well as spray our hats. I’ll need to repeat the treatment after six weeks or six washings—in late May, and again in July.

It seems to work. In 2015 and 2016, during the prime tick season of May and June, we would sometimes have between us as many as a dozen tick bites at one time. In 2017, after adopting Henry’s method, we had maybe three tick bites between us for the whole season. (When in the woods, we still tuck pant legs into socks.) Judging from its start (half-a-dozen pre-treatment tick bites already in early April), this may be a big year for ticks, so let’s hope it works.

In less frightening news, the official 2018 opening of the Quarry Gardens for individual tours is Friday, April 13. You can skip that one if you are a Triskaidekaphobe, but be warned that over 20 groups have already signed up for tours and many of the individual tour dates are filling up for April and May, so don’t delay if you want to schedule a visit.